Sanct-Petersburg Russia

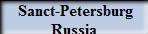

Joining of the Small Russia to the Moscow kingdom in 1654

Serafim Sarovsky, 1831

Saint Serafim Sarovsky.

A lifetime portrait.

A lifetime portrait.

Protoiereus George Florovsky

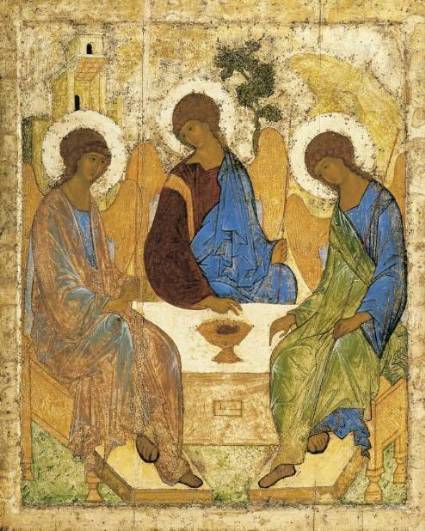

Andrey Rublev's Trinity

John Kronshtadsky. The rare image.

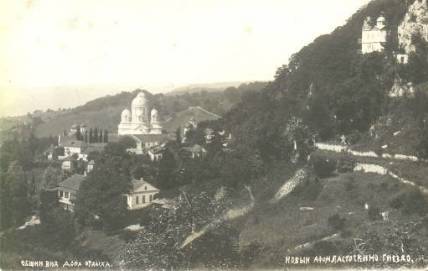

New Athon monastery in Abkhazia. Foto of early 20 century

Communion with God in the Russian Church was expressed in four forms: theology, hesychasts asceticism, icon-painting and liturgical ritual. The first of these forms (theology) had not managed to develop enough in Russia, and the next two (hesychasts mysticism and iconography) were

almost entirely destroyed or distorted in the 16th century. Basically the only one which survived was church liturgy: the last treasury preserving the achievements of Byzantine and Russian spirituality, the last living seed from which Russian Orthodoxy could be reborn in the future. The attempt to destroy this last stronghold was countered by the people with the Old Believers schism.

almost entirely destroyed or distorted in the 16th century. Basically the only one which survived was church liturgy: the last treasury preserving the achievements of Byzantine and Russian spirituality, the last living seed from which Russian Orthodoxy could be reborn in the future. The attempt to destroy this last stronghold was countered by the people with the Old Believers schism.

Patriarch Nikon was actually continuing the cause of Joseph and Macarius. Nikon's "graecophilia" was only formal - the soul of his reforms was Latinism. But he went further in this than his predecessors, raising the question of the power and role of the Pope. The essence of Catholicism is universal pastorage: the division of the Church into "teaching" and "learning", the organization of the clergy under the authoritarian power of the Pope and the subordinate position of secular authority in relation to church power. Nikon called himself "the pastor of the whole world" and persistently developed the idea that "the priesthood is higher than the tsarship". When Tsar Alexis went off to war, Nikon conducted all the business of state in his absence independently, held Councils and passed new laws. On his own initiative he published a new Book of Church Services, in the preface to which he announced publicly the "dyarchy" in Russia:

"God has chosen to rule and provide for His people this most wise pair, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich and the great Sovereign His Holiness Patriarch Nikon". The book urged "all those who live under their power, as under a united state rule, to rejoice".

Formally this could still be understood as a repetition of the symphony of Tsar and Patriarch, but Nikon wanted to go further: to turn into a rule the example of Patriarch Philaret Romanov who guided his son Michael in affairs of state. But neither the Tsar nor the boyars would agree to that.

Nikon's authoritarian reforms of the liturgy, which were introduced without preparing and convincing believers ignited the fire of Old Believer rebellion in Russia. Helpless in its theological arguments, deprived of the opportunity to develop, and lacking wise spiritual leaders, the Old Rite, which took away from the Church and the State the most sincere and active section of the people, was the Russian popular soul's instinctive, desperate reaction of self-preservation. Who knows where the irresponsible outburst of church reforms under Nikon, and then under Peter, Catherine II and Alexander I would have ended, in what Catholic or Protestant church future generations of Russian people would have had to worship, had the Old Believers not uttered their threatening and fanatical "No!" It is highly likely that without this frightening warning the Church and Russia would have lost their last sacred refuge, the last artery linking them with age-old Orthodox tradition would have been severed, the last source of spiritual hope for the future, the church's liturgical ritual, the most widespread and universal form of communing with God, would have been poisoned. Over every "reformer" there now hovered the fear that someone would rise up, like Avvakum, and say:

" Let us die for a single letter!"

Church services have a great, unceasing, constant, beneficial effect on the popular soul. Day after day, year after year, century after century, an endless human stream flows through the doors of Orthodox churches. In response to the appeal of tired people enmeshed in worldly cares the Church christens infants, buries the dead, hears the confessions of the penitent, marries the young, gives the Body and Blood of Christ in communion, prays for the sick, remembers departed kin, consecrates water, food and land, appeals to people's consciences and reminds them about God. Generation after generation arc nurtured by Russian women in the simple and wise truths which they have carried home from church; these truths they plant imperceptibly in the souls of their children; they nourish them with the spirit of life-loving patience, the meek, but inextinguishable hope of God's succor, the profound awareness of the meaning and endless significance of their stay on earth, no matter how many grievous trials and tribulations this life may bring. The foundation of the spiritual health and moral integrity of the Russian people was laid here over the centuries, No matter what forces attacked the Church, what temptations shook and undermined it from within, it always performed this service and continues to do so to this day. No matter how much one may grieve over its illnesses or lament the treasures winch it has lost on the path of history, this service by it should never be forgotten, and let no one ever throw stones at it...

The joining to the Moscow state of the Ukraine and Byelorussia under Tsar Alexis confronted the Tsar and the Patriarch with the difficult task of assimilating the Kievan metropolia which had been independent, of Moscow and formally subject to the Patriarch of Constantinople. Tins was not only a political, but first and foremost a spiritual task. The degree of Latinisation in Moscow and South Russian Orthodoxy differed. Under the influence of three centuries of Polish pressure the Ukraine had gone far "ahead" in this respect. The Orthodoxy of the Hundred Chapters was already unacceptable to Ukrainian Christianity as it was under Peter Mogila.

The alternative was either to force Moscow ways on the South Russian Church or to Latinize further oneself, to "reform" Moscow church life on Kievan lines. Alexis and Nikon chose the latter course. The Hundred Chapters was replaced by a new compilation of church laws called the "Sobornoe Ulozhenie" of 1649, a combination of the Lithuanian Statute and the Byzantine Nomokanon. The loss many years earlier of creative synergetic spirit and the consequent harsh formalization of Orthodoxy both in Moscow and in Kiev left Moscow will) only one choice - between a revolt by the Cossacks and a revolt by the Old-Riters. The Cossacks seemed more frightening... Alexis tried to satisfy both sides: to preserve the reforms, but to sacrifice Nikon. As a result there were two revolts! During the eight-year siege of Solovki defended by Old Believers, Razin led a revolt on the Don, spreading rumors that the innocently expelled Patriarch Nikon was in his camp together with the "Moscow tsarevich".`

Under Sophia and Theodore the Latin influence in Moscow increased even more, particularly after the conclusion of a "lasting peace" with Poland in 1686 and a military alliance with it against Turkey.

The struggle of Latin influences against Moscow tradition was at that time concentrated in the famous dispute "about the point at which the Holy Gifts were transubstantiated". Sylvester Medvedev, a man of broad education and considerable intelligence and a close friend of Shaklovity, the head of the Streltsy, preached the Latin view on this question. The power-loving Sophia supported Medvedev in this dispute, which did not prevent her from inflaming the Old Believer sympathies of the Streltsy at the same time.

When 17-year-old Peter imprisoned her in a convent, the power of the Church was for a while in the hands of Patriarch Joachim and Tsarina Natalia. Joachim began a program of anti-Latin national-church restoration, but did so with methods borrowed from the Catholic inquisition. Under him the Slavonic-Graeco-Latin Academy was obliged to ensure "purity of faith" and hand over those guilty of violations to the secular authorities for punishment. In 1690 a church council condemned Sylvester's doctrine as a heresy, the exile of Kievan scholarly monks from Moscow began and the practice of punishing people with different views at the hands. of the secular authorities was introduced.

This was the last attempt to restore to the Patriarchate the role and influence which it had possessed under Philaret and Nikon. Peter put an end to it firmly.

Russia had reached the historical age which demanded a rapid growth of the nation's personality, an expansion of its cultural horizons. Weakened by the struggle 'on two fronts' against Latinism and the Old Believers, having lost in the two hundred years since the defeat of the "Non-Possessors" the authority it had acquired during the age of Sergius and having stifled the energy of Christian creativity in itself through the Josephian reforms, the Russian Church of that day was quite incapable of leading the spiritual development of its people. Internally weakened, it could do nothing to resist Peter's despotism.

Peter produced his own answer to the challenge of history: not Latinism, the Greeks, or the Moscow tradition, but German Protestantism and Renaissance paganism were the spiritual movements which he found most promising and liberating for human creative activity. And this was in fact the case. Cut off from their Byzantine roots, both Roman Catholicism and Russian Orthodoxy had "frozen" within them the great spiritual potentials of Christianity. Of course, the path along which Peter led Russia took her even further from God, the Church and her age-old popular elements.

The Slavophiles, who saw the origin of Russia's troubles in Peter's "evil genius", were only half right: the main reason lay in the crisis of the Russian church itself. Peter's evil genius was only able to subject Russia because at that time the Church did not show Russians the truly Christian way of spiritual growth and development in order to lead the people along this path. The most energetic, educated and far-seeing members of Russian society were forced to follow Peter. They had nowhere else to go. To be against Peter meant to stand still or to go backwards. It was a bitter lesson for Russian Christianity.

Was this understood? And taken into account? Or did it still need the revolution of 1917? And is even that enough?

In accordance with his religious choice Peter replaced the image of Byzantine symphony by the ideal of the Roman Secular Empire. Dual church and secular rule was now at an end.

"From a single spiritual ruler the country can fear rebellions and revolts, for the common people do not know how to distinguish spiritual power from autocracy”, -

we read in Peter First's Church Statute (Dukhovny Reglament). To avoid such a "dyarchy" Peter abolished the Patriarchate and put a collegial Synod under a state official called the Ober-Prokuror in charge of church administration.

After Peter I the church policy of the Russian state fluctuated between one extreme and the other: the line changed with almost each new monarch. Catherine I tried to restore the religious foundation of tsarist rule. The "Testament" issued by her in 1727 states:

"No one may ever possess the Russian Throne who is not of the Greek law".

Peter II, the son of the executed Tsarevich Alexis, planned a whole program of returning to the old customs. Under him the Imperial court moved hack to Moscow and preparations were made to restore the Patriarchate. The candidate was Russian, Georgy Dashkov, Metropolitan of Rostov, which was an obvious challenge to the domination by the Ukrainian higher clergy established under Peter I ("seventy years of Babylonian captivity", as the Russian hierarchs referred to it with bitter humor). Empress Anne put an end to all these attempts, handling over the clergy "to be torn to pieces" by Feofan Prokopovich. No one dared to say a word about the patriarchate and Moscow traditions in her day. Elizabeth kept the Church in the same position, whereas her nephew Peter III was openly hostile to it. Although only six months on the throne, he managed to issue a decree on the complete secularization of church and monastery lands which had been drafted during Elizabeth's reign. Catherine II finished this off. As a result of her secularization of the 732 monasteries and 232 convents in Russia, only 161 and 39 remained respectively.

As Alexander Pushkin, who studied the history of this period, concluded, by closing the monasteries Catherine II dealt an irreparable blow to Russian enlightenment. Unlike her luckless husband, Catherine took away Church lands not by Imperial decree, but by the hands of the archbishops themselves. On Catherine's orders Metropolitan Dmitri (Sechenov) of Novgorod, the "president" of the Holy Synod deleted from the Rite of Orthodoxy all ex-communications "which encroach upon church estates". His successor Gavriil (Petrov), realizing that it was hopeless to struggle against the Imperial power, took upon himself the responsibility for secularization.

The time had come to turn to the forgotten experience of the "Non-Possessors" who, at the beginning of the 16th century had preached the voluntary renunciation of monastic land-holding. Following their example, Metropolitan Gavriil began to establish monastic "anachoretism", to revive the traditions of Orthodox elders. The revering of the "great elder" Nil Sorsky was revived and monasteries were based on his Rule. Russian monks were drawn to Mount Athos to obtain experience of spiritual life.

A center of this new (although actually old) type of anchorite monasticism in Russia was Paissy Velichkovsky's monastery in Moldavia, which had over 1,000 monks. Here the Hesychast practice of "mindful-heartfelt doing" was restored and traditional "book" culture - the translation and study of the Church among the people.

The famous Optina Pustyn was soon flourishing, where the educated classes of society were able to receive spiritual nourishment. The cooperation of the Slavophile members of the nobility with this monastery gave rise to such a splendid form of church-cultural service as the Optino book publishing, which played a considerable role in the new awakening of Russian spirituality. The most outstanding of the Optino elders was Ambrose, who was canonized by the Local Council of 1988. Ambrose was visited by many eminent figures in Russian culture: P.M. Dostoevsky, V.S. Solovyov, K. Leontiev, A.K. Tolstoy, M.P. Pogodin, P.D. Yurkevich, N.N. Strachov and V.V. Rozanov. Lev Tolstoy also had several meetings with Ambrose. It was here, to Optino, hat he hastened in his last "flight" just before his death. Theophanes the Recluse, also canonized in 1988, put a great deal of effort into restoring the Eastern Orthodox tradition. The seven years which he spent in the Orthodox East (as a member of the Russian Spiritual Mission in Jerusalem) opened up the ecumenical horizons of Christianity to him. Here he immersed himself in reading old church books, came into personal spiritual contact with the elders of Mount Athos and spent much time talking and disputing with Catholic and Protestant priests. After his journey round Europe, lie adopted a clearly "Graecophile" position.

"The disunity with the Eastern or Greek church, - wrote Feofan, - is a great evil for Russia. The darkness comes of the west, yet we refuse to accept the light from the east... Do not praise the Russia of today. Rather reproach it for going the wrong way since it became acquainted with the west".

One cannot help being amazed by the number of Theophanes' works and the ecumenical breadth of his interests, which is characteristic of the synergetic humanism of freedom of the spirit.

"We are quite justified," wrote one his biographers, "in calling him the great sage of Christian philosophy. He is as fruitful as the Holy Fathers of the fourth century."

The Whole Russian 19th century was illumined from within, as it were by the clear and powerful radiance from that great zealot of the Russian Land - the Venerable Seraphim of Sara. Canonized in 1903 on the personal instructions of Nicholas II, the Venerable Seraphim immediately found himself side by side with Sergius of Radonezh in the popular consciousness They arc united not only by the fact that they are the two most revered Russian saints. They also have much in common in the character of their spiritual make-up.

Like Sergius, Seraphim was deeply rooted in the Hesychast Byzantine tradition and, also like Sergius, strove for an apocalyptic view. Seraphim's teaching on attaining the Spirit of God as the aim of Christian life is basically the same as Palamism. The experience of the "Tabor transfiguration" to which Seraphim introduced his disciple Motovilov corresponds exactly to Gregory Palamas teaching on Divine Energy. Seraphim was also one of the greatest Russian "elders". He constantly exhorted his brothers in prayer:

"My joy, I beg you, attain peace of spirit, and thousands of souls will salve themselves around you.

Many thousands of Russian people grazed around Seraphim himself and this spiritual zealot who had emerged from many years of retreat never turned anyone away. A new feature of Seraphim in contrast to Sergius is the revelation about womanhood. Whereas Sergius created

sobornost as a male brotherhood, the secret of female sobornost was also revealed to Seraphim. His vita tells about Ins unique spiritual experience - the appearance to Seraphim and the Diveyevo sisters of the Virgin Mary accompanied by twelve holy maidens. During a long talk the Virgin Mary explained to Seraphim that "these maidens were for her the same as the apostles for Christ."

All the Venerable Seraphim's service is full of a paschal apocalyptic joy - in this he also resembles the saint of Sergius' circle. Seraphim addresses every newcomer as "my joy!" His nuns are robed in white instead of black. The Diveyevo chronicles have preserved Seraphim's prophecy about the tsar's family visiting Diveyevo; about the defence of the place against the Anti-Christ; about the “four appanages (allotments) of the Theotokos" - Iberia (the present Abkhazia), Athos, Kiev and Diveyevo; about the future personal resurrection of Seraphim and some of his nuns before the eyes of all "in witness of universal resurrection", etc. These chronicles may include some apocryphas, of course, but the very character of the legends reflects the general spiritual mood of this great elder of the Russian Land. And in the tragic 20th century, full of apocalyptic omens perhaps no other saint has had so many heartfelt appeals, addressed to him.

"Venerable Father Seraphim, pray to God for us"!

* * *

In the 19th century when theological thought began to revive in Russia and seek roots in the patristic and liturgical tradition, it immediately came up against powerful layers of extra-Christian or even anti-Christian European culture. And, of course, Orthodox thought, which was only just emerging from its long torpor, was almost helpless in the face of this cultural challenge. The three hundred years which had been lost for spiritual development made themselves felt. Let us try for a moment to imagine what Russian Orthodox culture could have been like by the end of the 19th century, if the age of Sergius theology and Rublev's icon-painting had been not its height, but merely the point of departure for further uninterrupted growth. And what it could have been like now...

While Russian Orthodox thought was stagnating in immobility and being nourished, not by the living patristic word but by the dead food of Jesuit scholastics which had been implanted in church schools ever since the Petrine period, extra-church culture dealt Christian culture some terrible, destructive blows, depriving it of the initiative in the cultural development of mankind. Newton, Darwin, Kant, and at the end of the 19th century Nietzsche and Marx ruled the minds of European mankind, which had long since forgotten about the Christianity of the Church Fathers as a source of creative answers to all the challenges of the guesting spirit, to all the questions of inquiring human thought. Cultural mankind was learning more and more to manage without God and His Energy.

Russian religious thought of the early 20th century was a noble, heroic attempt to answer this challenge or at least accept it with dignity. This philosophy showed that Orthodox thought was capable of a real dialogue with European culture - a truly historic achievement. Yet for all the creative power of its founders, this philosophy itself was still divided. It was not yet fully Orthodox and still needed to be nurtured by alien sources of mystical experience.

The most authoritative Orthodox theologian of the 20th century, Archpriest George Florovsky (see his work: "Puti russkogo bogosloviya". Paris. IMCA, 1937) argued that through all the so-called "new religious consciousness" there ran a stream of "mystical temptation", i.e., a confusion of human and Divine essences. But tins does not invalidate the cultural and spiritual value of Russian religious philosophy - in the boldness and depth of its questions, in its universal dimensions, in the sincerity of its self-expression of personality it is unequalled in the history of European thought. The best that is in it was acquired as a result of deep excavations, as it were, painful recollection, breaking though the tough membrane of the seeds of patristic thought, conserved and turned into "disputes", but still viable. At the same time the experience of Russian philosophy showed that for true Orthodox creativity like that of Rublev, it was necessary not only to cultivate what had been sown many centuries before, but also to have a constant outflow of life-giving patristic spirit, constant communion with the eternally new and reborn patristic word. But prerevolutionary Russia did not manage to acquire such a source.

The beginning of the 20th century revived, as it were, at a deeper level the spiritual ferment and apocalyptic mood of the age of Alexander I. Nicholas II himself by his religious quests was very lose to it, and also died a saint's death, only not that of a venerable elder, but also that of a martyr. (The well-known legend about "the elder Fyodor Kuzmich" which claims that the Emperor Alexander I only pretended to die in Taganrog seems to us to be perfectly likely).

The mystical tension of the age also expressed itself in a revival of popular sectarianism, in the "new religious consciousness" of the freshly converted intelligentsia, in the political presentiments of imminent cataclysms, in impetuous projects of social reorganization, in the khlyst-orgies of Rasputin, in Badmayev oriental mysticism and in the broad influx of spiritualism and theosophy.

One of the most eloquent testimonies to the spirit of the age were the Religious-Philosophical meetings in St Petersburg, where in free dialogue the religious intelligentsia met representatives of the church clergy (the meetings were chaired by Bishop Sergius Stragorodsky). The church and society, faith and reason, sex and asceticism, tradition and renewal, individualism and "sobornost" these subjects were carried all over Russia in the publications of the meetings. The apocalyptic leitmotif dominated in many addresses.

"Faith in a just land promised by God through the prophets," said the eminent churchman Ternavtsev, for example, "tins is the sort of secret that must be revealed. But this revelation about the land is a new revelation about man. The tight confines of individuality in winch all souls now languish are collapsing. The earth with the opened heavens above it will become the field of a new supra-historical life... The question of Christ will become for authority a question of life or death "with a most profound religious-sacrificial meaning. This is new in Christianity and herein lies for Russia the path of religious creativity and the revelation of universal salvation..."

The communist idea in Russia was first seen as the idea of sobornost transferred to "real soil". Chernyshevsky's "crystal palaces" turned the heads of many future revolutionaries and god-seekers. Later some thinkers were to detect even the roots of totalitarianism in Christian church sobornost (for example, Zamyatin in his anti-utopia "We").

Yet does Rublev's "Trinity", that supreme image of sobornost, contain the slightest hint of the totalitarian suppression of the individual? Is it not imbued with the spirit of freedom and love?

Thanks to the efforts of restorers this icon was itself only revealed to the amazed eyes of mankind at the beginning of the 20th century, as an answer to the general questioning about the essence and nature of the sobornost element. It was precise at the time when it seemed as if Holy Russia were disappearing forever into oblivion, that Rublev's "Trinity" appeared as a revelation of the popular soul, providing a bridge across the centuries of darkness to the 15th century, the most "Russian" and most "Christian" century in Russian history. Its immortal beauty shone out over the abyss of popular suffering, generation upon generation of Russian people absorbed through it the living spirit of true Christian sobornost. We have already learnt to admire the beauty of the image of the Holy Trinity, but the discovery of the deep layers of meaning in this icon has yet to come...

There is no sobornost outside the Church, this is the main, if negative result of the Russian intelligentsia's sincere and creative searchings. But is there any inside the Church? The beginning of sobornost is the Tri-Une God, the Holy Trinity: in human nature, which is intrinsically individualistic, only God himself can arouse a real, free desire for sobornost.

But this will be possible only when man is free and able to devote himself all the time to God, to entrust Him with arousing in people the most profound and intimate desires and thoughts, beginning with the original will to live and be. Original sin is precisely that Man rejected this and began to look for the foundation of his being in all sorts of other things: in nature, in the national, in the Weltgeist, in himself, only not in Got. Thus a vicious circle arose, condemning man to destruction, to the loss sooner or later of the will to live, which lies at the basis of man's existence.

The sobornost of the Church is rooted in Communion in the nature of Jesus Christ. "The Church is the Eucharist," said one of the ancient fathers. It is no accident that the restoration of sobornost in the Russian Church began with the "Eucharistic revival", a movement connected with the name of that great saint of the pre-revolutionary period, Father John of Kronstadt. After Seraphim of Sarov, Ambrose of Optino and Theophanes the Recluse, John of Kronstadt is the type of Hesychast zealot in which experience of knowing God is combined with theological intellect, spiritual "reclusion" with varied service of the world. What was new and unheard-of in the history of the Russian Church was the fact that John of Kronstadt, a typical "venerable" monk in the nature of his spiritual feat, was not a monk at all, but a married "white" priest. An ardent preacher of the Eucharist, Father John witnessed with all his being that the human body together with the soul is called to sanctity, which does not exclude married life. The spirit of Manichaeism, squeamish with regard to Divine creation, a spirit which poisoned the religious psychology of a believing people, was rejected here totally. In the writings of Gregory Palamas the Grace of God, which he understood as the Divine Energy, says to a believer:

"Do you not want to trust yourself to me completely as a monk?... And with a chaste wife beloved by you I greet you and accept you none the less..."

The 20th-century Russian Athonite zealot, the elder Siluan, wrote of John of Kronstadt:

"Some think badly of Father John, and in so doing offend the Holy Spirit Who dwells in him and lives after death. They say that he was rich and dressed well. But they do not know that he in whom the Holy Spirit dwells is not harmed by riches, for his soul is all in God, and it was changed by God and forgot its riches and fine dress. Happy are those who love Father John, for he will pray for us. His love of God is ardent; he is all in a flame of love".Archpriest Sofrony. The Starets Siluan. Paris. 1952, p. 195.

As a result of Father John's great authority and influence the Eucharist again became the focal point of church life. He demanded that people take communion as often as possible, preferably once a week, for which he greatly reduced the requirements of fasting before communion; he recommended general confession, allowing priests to give communion to a large number of believers at once. This was a change in the main guidelines of the parish consciousness, if one remembers that before it was considered quite enough to take communion once a year, and communion itself was regarded as an addition to Lent. The "Eucharistic revival" returned the center of gravity of church life from psychology to ontology, from moralism to synergetic spirituality.

A powerful upsurge of Hesychasm under the name of lmyaslavie came to Russian from Mount Athos at the beginning of the 20th century.

Among the many Russian monks on Mount Athos at that time a dogmatic dispute arose on the nature of the name "Jesus". The lmyaslavtsy ("name-extollers") claimed that it was Divine, whereas the lmyabortsy ("name-combatters") denied this, and most aggressively too. this was essentially a continuation of the Palamite disputes on the 14th century of the Divine or human nature of the light which Jesus showed his disciples on Mount Tabor.

The disorders which arose on Mount Athos necessitated the intervention of the Greek police. More that 600 lmyslavtsy were forcibly sent to Russia in order to be judged by the church authorities. They found defenders in court circles. The matter received a lot of publicity and was even discussed in the State Duma, much to the embarrassment of "enlightened" deputies, who were amazed by this, as they put it, "return to the Middle Ages".

The matter ended with the Holy Synod adopting an extremely negative attitude to lmyaslavie, making use of the inaccuracy of the theological formulations with which the Russian Hesychasts tried to express their experience of knowing God. The scholastics on which the theological consciousness of the Russian clergy was based left no place for such religious experience. When similar disputes arose in Byzantine it took great efforts of theological thought, crowned by the works of Gregory Palamas, to express, argue and establish in words the Hesychasts spiritual experience. The Russian lmyaslavtsy had no knowledge of Palamas dogmatic doctrine, however. Nor had he been studied in their seminaries by the members of the Holy Synod who found the lmyaslavtsy guilty of "heresy" (the Synod members included Archbishop Sergius Stragorodsky). Fragments of the dogmatic resolutions of the Constantinopolitan "Palamite" councils were first translated into Russian by the philosopher Alexei Losev in the late 1920s! The lmyslavtsy were defended by Father Sergius Bulgakov and Patriarch Tikhon felt sympathy for them, but this was already too late. In the Synod's resolution of 1911 the lmyaslavtsy were found guilty and sent "for correction" in small groups to various Russian monasteries. The result was that their practice of prayer spread throughout the whole of Russian monasticism. The main base for Russian Hesychasts became the numerous monasteries in the Caucasus mountains, which relied for support on the mighty monastery of Novy Afon in Abkhazia.

* * *

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

almost entirely destroyed or distorted in the 16th century. Basically the only one which survived was church liturgy: the last treasury preserving the achievements of Byzantine and Russian spirituality, the last living seed from which Russian Orthodoxy could be reborn in the future. The attempt to destroy this last stronghold was countered by the people with the Old Believers schism.

almost entirely destroyed or distorted in the 16th century. Basically the only one which survived was church liturgy: the last treasury preserving the achievements of Byzantine and Russian spirituality, the last living seed from which Russian Orthodoxy could be reborn in the future. The attempt to destroy this last stronghold was countered by the people with the Old Believers schism.Patriarch Nikon was actually continuing the cause of Joseph and Macarius. Nikon's "graecophilia" was only formal - the soul of his reforms was Latinism. But he went further in this than his predecessors, raising the question of the power and role of the Pope. The essence of Catholicism is universal pastorage: the division of the Church into "teaching" and "learning", the organization of the clergy under the authoritarian power of the Pope and the subordinate position of secular authority in relation to church power. Nikon called himself "the pastor of the whole world" and persistently developed the idea that "the priesthood is higher than the tsarship". When Tsar Alexis went off to war, Nikon conducted all the business of state in his absence independently, held Councils and passed new laws. On his own initiative he published a new Book of Church Services, in the preface to which he announced publicly the "dyarchy" in Russia:

"God has chosen to rule and provide for His people this most wise pair, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich and the great Sovereign His Holiness Patriarch Nikon". The book urged "all those who live under their power, as under a united state rule, to rejoice".

Formally this could still be understood as a repetition of the symphony of Tsar and Patriarch, but Nikon wanted to go further: to turn into a rule the example of Patriarch Philaret Romanov who guided his son Michael in affairs of state. But neither the Tsar nor the boyars would agree to that.

Nikon's authoritarian reforms of the liturgy, which were introduced without preparing and convincing believers ignited the fire of Old Believer rebellion in Russia. Helpless in its theological arguments, deprived of the opportunity to develop, and lacking wise spiritual leaders, the Old Rite, which took away from the Church and the State the most sincere and active section of the people, was the Russian popular soul's instinctive, desperate reaction of self-preservation. Who knows where the irresponsible outburst of church reforms under Nikon, and then under Peter, Catherine II and Alexander I would have ended, in what Catholic or Protestant church future generations of Russian people would have had to worship, had the Old Believers not uttered their threatening and fanatical "No!" It is highly likely that without this frightening warning the Church and Russia would have lost their last sacred refuge, the last artery linking them with age-old Orthodox tradition would have been severed, the last source of spiritual hope for the future, the church's liturgical ritual, the most widespread and universal form of communing with God, would have been poisoned. Over every "reformer" there now hovered the fear that someone would rise up, like Avvakum, and say:

" Let us die for a single letter!"

Church services have a great, unceasing, constant, beneficial effect on the popular soul. Day after day, year after year, century after century, an endless human stream flows through the doors of Orthodox churches. In response to the appeal of tired people enmeshed in worldly cares the Church christens infants, buries the dead, hears the confessions of the penitent, marries the young, gives the Body and Blood of Christ in communion, prays for the sick, remembers departed kin, consecrates water, food and land, appeals to people's consciences and reminds them about God. Generation after generation arc nurtured by Russian women in the simple and wise truths which they have carried home from church; these truths they plant imperceptibly in the souls of their children; they nourish them with the spirit of life-loving patience, the meek, but inextinguishable hope of God's succor, the profound awareness of the meaning and endless significance of their stay on earth, no matter how many grievous trials and tribulations this life may bring. The foundation of the spiritual health and moral integrity of the Russian people was laid here over the centuries, No matter what forces attacked the Church, what temptations shook and undermined it from within, it always performed this service and continues to do so to this day. No matter how much one may grieve over its illnesses or lament the treasures winch it has lost on the path of history, this service by it should never be forgotten, and let no one ever throw stones at it...

The joining to the Moscow state of the Ukraine and Byelorussia under Tsar Alexis confronted the Tsar and the Patriarch with the difficult task of assimilating the Kievan metropolia which had been independent, of Moscow and formally subject to the Patriarch of Constantinople. Tins was not only a political, but first and foremost a spiritual task. The degree of Latinisation in Moscow and South Russian Orthodoxy differed. Under the influence of three centuries of Polish pressure the Ukraine had gone far "ahead" in this respect. The Orthodoxy of the Hundred Chapters was already unacceptable to Ukrainian Christianity as it was under Peter Mogila.

The alternative was either to force Moscow ways on the South Russian Church or to Latinize further oneself, to "reform" Moscow church life on Kievan lines. Alexis and Nikon chose the latter course. The Hundred Chapters was replaced by a new compilation of church laws called the "Sobornoe Ulozhenie" of 1649, a combination of the Lithuanian Statute and the Byzantine Nomokanon. The loss many years earlier of creative synergetic spirit and the consequent harsh formalization of Orthodoxy both in Moscow and in Kiev left Moscow will) only one choice - between a revolt by the Cossacks and a revolt by the Old-Riters. The Cossacks seemed more frightening... Alexis tried to satisfy both sides: to preserve the reforms, but to sacrifice Nikon. As a result there were two revolts! During the eight-year siege of Solovki defended by Old Believers, Razin led a revolt on the Don, spreading rumors that the innocently expelled Patriarch Nikon was in his camp together with the "Moscow tsarevich".`

Under Sophia and Theodore the Latin influence in Moscow increased even more, particularly after the conclusion of a "lasting peace" with Poland in 1686 and a military alliance with it against Turkey.

The struggle of Latin influences against Moscow tradition was at that time concentrated in the famous dispute "about the point at which the Holy Gifts were transubstantiated". Sylvester Medvedev, a man of broad education and considerable intelligence and a close friend of Shaklovity, the head of the Streltsy, preached the Latin view on this question. The power-loving Sophia supported Medvedev in this dispute, which did not prevent her from inflaming the Old Believer sympathies of the Streltsy at the same time.

When 17-year-old Peter imprisoned her in a convent, the power of the Church was for a while in the hands of Patriarch Joachim and Tsarina Natalia. Joachim began a program of anti-Latin national-church restoration, but did so with methods borrowed from the Catholic inquisition. Under him the Slavonic-Graeco-Latin Academy was obliged to ensure "purity of faith" and hand over those guilty of violations to the secular authorities for punishment. In 1690 a church council condemned Sylvester's doctrine as a heresy, the exile of Kievan scholarly monks from Moscow began and the practice of punishing people with different views at the hands. of the secular authorities was introduced.

This was the last attempt to restore to the Patriarchate the role and influence which it had possessed under Philaret and Nikon. Peter put an end to it firmly.

Russia had reached the historical age which demanded a rapid growth of the nation's personality, an expansion of its cultural horizons. Weakened by the struggle 'on two fronts' against Latinism and the Old Believers, having lost in the two hundred years since the defeat of the "Non-Possessors" the authority it had acquired during the age of Sergius and having stifled the energy of Christian creativity in itself through the Josephian reforms, the Russian Church of that day was quite incapable of leading the spiritual development of its people. Internally weakened, it could do nothing to resist Peter's despotism.

Peter produced his own answer to the challenge of history: not Latinism, the Greeks, or the Moscow tradition, but German Protestantism and Renaissance paganism were the spiritual movements which he found most promising and liberating for human creative activity. And this was in fact the case. Cut off from their Byzantine roots, both Roman Catholicism and Russian Orthodoxy had "frozen" within them the great spiritual potentials of Christianity. Of course, the path along which Peter led Russia took her even further from God, the Church and her age-old popular elements.

The Slavophiles, who saw the origin of Russia's troubles in Peter's "evil genius", were only half right: the main reason lay in the crisis of the Russian church itself. Peter's evil genius was only able to subject Russia because at that time the Church did not show Russians the truly Christian way of spiritual growth and development in order to lead the people along this path. The most energetic, educated and far-seeing members of Russian society were forced to follow Peter. They had nowhere else to go. To be against Peter meant to stand still or to go backwards. It was a bitter lesson for Russian Christianity.

Was this understood? And taken into account? Or did it still need the revolution of 1917? And is even that enough?

In accordance with his religious choice Peter replaced the image of Byzantine symphony by the ideal of the Roman Secular Empire. Dual church and secular rule was now at an end.

"From a single spiritual ruler the country can fear rebellions and revolts, for the common people do not know how to distinguish spiritual power from autocracy”, -

we read in Peter First's Church Statute (Dukhovny Reglament). To avoid such a "dyarchy" Peter abolished the Patriarchate and put a collegial Synod under a state official called the Ober-Prokuror in charge of church administration.

After Peter I the church policy of the Russian state fluctuated between one extreme and the other: the line changed with almost each new monarch. Catherine I tried to restore the religious foundation of tsarist rule. The "Testament" issued by her in 1727 states:

"No one may ever possess the Russian Throne who is not of the Greek law".

Peter II, the son of the executed Tsarevich Alexis, planned a whole program of returning to the old customs. Under him the Imperial court moved hack to Moscow and preparations were made to restore the Patriarchate. The candidate was Russian, Georgy Dashkov, Metropolitan of Rostov, which was an obvious challenge to the domination by the Ukrainian higher clergy established under Peter I ("seventy years of Babylonian captivity", as the Russian hierarchs referred to it with bitter humor). Empress Anne put an end to all these attempts, handling over the clergy "to be torn to pieces" by Feofan Prokopovich. No one dared to say a word about the patriarchate and Moscow traditions in her day. Elizabeth kept the Church in the same position, whereas her nephew Peter III was openly hostile to it. Although only six months on the throne, he managed to issue a decree on the complete secularization of church and monastery lands which had been drafted during Elizabeth's reign. Catherine II finished this off. As a result of her secularization of the 732 monasteries and 232 convents in Russia, only 161 and 39 remained respectively.

As Alexander Pushkin, who studied the history of this period, concluded, by closing the monasteries Catherine II dealt an irreparable blow to Russian enlightenment. Unlike her luckless husband, Catherine took away Church lands not by Imperial decree, but by the hands of the archbishops themselves. On Catherine's orders Metropolitan Dmitri (Sechenov) of Novgorod, the "president" of the Holy Synod deleted from the Rite of Orthodoxy all ex-communications "which encroach upon church estates". His successor Gavriil (Petrov), realizing that it was hopeless to struggle against the Imperial power, took upon himself the responsibility for secularization.

The time had come to turn to the forgotten experience of the "Non-Possessors" who, at the beginning of the 16th century had preached the voluntary renunciation of monastic land-holding. Following their example, Metropolitan Gavriil began to establish monastic "anachoretism", to revive the traditions of Orthodox elders. The revering of the "great elder" Nil Sorsky was revived and monasteries were based on his Rule. Russian monks were drawn to Mount Athos to obtain experience of spiritual life.

A center of this new (although actually old) type of anchorite monasticism in Russia was Paissy Velichkovsky's monastery in Moldavia, which had over 1,000 monks. Here the Hesychast practice of "mindful-heartfelt doing" was restored and traditional "book" culture - the translation and study of the Church among the people.

The famous Optina Pustyn was soon flourishing, where the educated classes of society were able to receive spiritual nourishment. The cooperation of the Slavophile members of the nobility with this monastery gave rise to such a splendid form of church-cultural service as the Optino book publishing, which played a considerable role in the new awakening of Russian spirituality. The most outstanding of the Optino elders was Ambrose, who was canonized by the Local Council of 1988. Ambrose was visited by many eminent figures in Russian culture: P.M. Dostoevsky, V.S. Solovyov, K. Leontiev, A.K. Tolstoy, M.P. Pogodin, P.D. Yurkevich, N.N. Strachov and V.V. Rozanov. Lev Tolstoy also had several meetings with Ambrose. It was here, to Optino, hat he hastened in his last "flight" just before his death. Theophanes the Recluse, also canonized in 1988, put a great deal of effort into restoring the Eastern Orthodox tradition. The seven years which he spent in the Orthodox East (as a member of the Russian Spiritual Mission in Jerusalem) opened up the ecumenical horizons of Christianity to him. Here he immersed himself in reading old church books, came into personal spiritual contact with the elders of Mount Athos and spent much time talking and disputing with Catholic and Protestant priests. After his journey round Europe, lie adopted a clearly "Graecophile" position.

"The disunity with the Eastern or Greek church, - wrote Feofan, - is a great evil for Russia. The darkness comes of the west, yet we refuse to accept the light from the east... Do not praise the Russia of today. Rather reproach it for going the wrong way since it became acquainted with the west".

One cannot help being amazed by the number of Theophanes' works and the ecumenical breadth of his interests, which is characteristic of the synergetic humanism of freedom of the spirit.

"We are quite justified," wrote one his biographers, "in calling him the great sage of Christian philosophy. He is as fruitful as the Holy Fathers of the fourth century."

The Whole Russian 19th century was illumined from within, as it were by the clear and powerful radiance from that great zealot of the Russian Land - the Venerable Seraphim of Sara. Canonized in 1903 on the personal instructions of Nicholas II, the Venerable Seraphim immediately found himself side by side with Sergius of Radonezh in the popular consciousness They arc united not only by the fact that they are the two most revered Russian saints. They also have much in common in the character of their spiritual make-up.

Like Sergius, Seraphim was deeply rooted in the Hesychast Byzantine tradition and, also like Sergius, strove for an apocalyptic view. Seraphim's teaching on attaining the Spirit of God as the aim of Christian life is basically the same as Palamism. The experience of the "Tabor transfiguration" to which Seraphim introduced his disciple Motovilov corresponds exactly to Gregory Palamas teaching on Divine Energy. Seraphim was also one of the greatest Russian "elders". He constantly exhorted his brothers in prayer:

"My joy, I beg you, attain peace of spirit, and thousands of souls will salve themselves around you.

Many thousands of Russian people grazed around Seraphim himself and this spiritual zealot who had emerged from many years of retreat never turned anyone away. A new feature of Seraphim in contrast to Sergius is the revelation about womanhood. Whereas Sergius created

sobornost as a male brotherhood, the secret of female sobornost was also revealed to Seraphim. His vita tells about Ins unique spiritual experience - the appearance to Seraphim and the Diveyevo sisters of the Virgin Mary accompanied by twelve holy maidens. During a long talk the Virgin Mary explained to Seraphim that "these maidens were for her the same as the apostles for Christ."

All the Venerable Seraphim's service is full of a paschal apocalyptic joy - in this he also resembles the saint of Sergius' circle. Seraphim addresses every newcomer as "my joy!" His nuns are robed in white instead of black. The Diveyevo chronicles have preserved Seraphim's prophecy about the tsar's family visiting Diveyevo; about the defence of the place against the Anti-Christ; about the “four appanages (allotments) of the Theotokos" - Iberia (the present Abkhazia), Athos, Kiev and Diveyevo; about the future personal resurrection of Seraphim and some of his nuns before the eyes of all "in witness of universal resurrection", etc. These chronicles may include some apocryphas, of course, but the very character of the legends reflects the general spiritual mood of this great elder of the Russian Land. And in the tragic 20th century, full of apocalyptic omens perhaps no other saint has had so many heartfelt appeals, addressed to him.

"Venerable Father Seraphim, pray to God for us"!

* * *

In the 19th century when theological thought began to revive in Russia and seek roots in the patristic and liturgical tradition, it immediately came up against powerful layers of extra-Christian or even anti-Christian European culture. And, of course, Orthodox thought, which was only just emerging from its long torpor, was almost helpless in the face of this cultural challenge. The three hundred years which had been lost for spiritual development made themselves felt. Let us try for a moment to imagine what Russian Orthodox culture could have been like by the end of the 19th century, if the age of Sergius theology and Rublev's icon-painting had been not its height, but merely the point of departure for further uninterrupted growth. And what it could have been like now...

While Russian Orthodox thought was stagnating in immobility and being nourished, not by the living patristic word but by the dead food of Jesuit scholastics which had been implanted in church schools ever since the Petrine period, extra-church culture dealt Christian culture some terrible, destructive blows, depriving it of the initiative in the cultural development of mankind. Newton, Darwin, Kant, and at the end of the 19th century Nietzsche and Marx ruled the minds of European mankind, which had long since forgotten about the Christianity of the Church Fathers as a source of creative answers to all the challenges of the guesting spirit, to all the questions of inquiring human thought. Cultural mankind was learning more and more to manage without God and His Energy.

Russian religious thought of the early 20th century was a noble, heroic attempt to answer this challenge or at least accept it with dignity. This philosophy showed that Orthodox thought was capable of a real dialogue with European culture - a truly historic achievement. Yet for all the creative power of its founders, this philosophy itself was still divided. It was not yet fully Orthodox and still needed to be nurtured by alien sources of mystical experience.

The most authoritative Orthodox theologian of the 20th century, Archpriest George Florovsky (see his work: "Puti russkogo bogosloviya". Paris. IMCA, 1937) argued that through all the so-called "new religious consciousness" there ran a stream of "mystical temptation", i.e., a confusion of human and Divine essences. But tins does not invalidate the cultural and spiritual value of Russian religious philosophy - in the boldness and depth of its questions, in its universal dimensions, in the sincerity of its self-expression of personality it is unequalled in the history of European thought. The best that is in it was acquired as a result of deep excavations, as it were, painful recollection, breaking though the tough membrane of the seeds of patristic thought, conserved and turned into "disputes", but still viable. At the same time the experience of Russian philosophy showed that for true Orthodox creativity like that of Rublev, it was necessary not only to cultivate what had been sown many centuries before, but also to have a constant outflow of life-giving patristic spirit, constant communion with the eternally new and reborn patristic word. But prerevolutionary Russia did not manage to acquire such a source.

The beginning of the 20th century revived, as it were, at a deeper level the spiritual ferment and apocalyptic mood of the age of Alexander I. Nicholas II himself by his religious quests was very lose to it, and also died a saint's death, only not that of a venerable elder, but also that of a martyr. (The well-known legend about "the elder Fyodor Kuzmich" which claims that the Emperor Alexander I only pretended to die in Taganrog seems to us to be perfectly likely).

The mystical tension of the age also expressed itself in a revival of popular sectarianism, in the "new religious consciousness" of the freshly converted intelligentsia, in the political presentiments of imminent cataclysms, in impetuous projects of social reorganization, in the khlyst-orgies of Rasputin, in Badmayev oriental mysticism and in the broad influx of spiritualism and theosophy.

One of the most eloquent testimonies to the spirit of the age were the Religious-Philosophical meetings in St Petersburg, where in free dialogue the religious intelligentsia met representatives of the church clergy (the meetings were chaired by Bishop Sergius Stragorodsky). The church and society, faith and reason, sex and asceticism, tradition and renewal, individualism and "sobornost" these subjects were carried all over Russia in the publications of the meetings. The apocalyptic leitmotif dominated in many addresses.

"Faith in a just land promised by God through the prophets," said the eminent churchman Ternavtsev, for example, "tins is the sort of secret that must be revealed. But this revelation about the land is a new revelation about man. The tight confines of individuality in winch all souls now languish are collapsing. The earth with the opened heavens above it will become the field of a new supra-historical life... The question of Christ will become for authority a question of life or death "with a most profound religious-sacrificial meaning. This is new in Christianity and herein lies for Russia the path of religious creativity and the revelation of universal salvation..."

The communist idea in Russia was first seen as the idea of sobornost transferred to "real soil". Chernyshevsky's "crystal palaces" turned the heads of many future revolutionaries and god-seekers. Later some thinkers were to detect even the roots of totalitarianism in Christian church sobornost (for example, Zamyatin in his anti-utopia "We").

Yet does Rublev's "Trinity", that supreme image of sobornost, contain the slightest hint of the totalitarian suppression of the individual? Is it not imbued with the spirit of freedom and love?

Thanks to the efforts of restorers this icon was itself only revealed to the amazed eyes of mankind at the beginning of the 20th century, as an answer to the general questioning about the essence and nature of the sobornost element. It was precise at the time when it seemed as if Holy Russia were disappearing forever into oblivion, that Rublev's "Trinity" appeared as a revelation of the popular soul, providing a bridge across the centuries of darkness to the 15th century, the most "Russian" and most "Christian" century in Russian history. Its immortal beauty shone out over the abyss of popular suffering, generation upon generation of Russian people absorbed through it the living spirit of true Christian sobornost. We have already learnt to admire the beauty of the image of the Holy Trinity, but the discovery of the deep layers of meaning in this icon has yet to come...

There is no sobornost outside the Church, this is the main, if negative result of the Russian intelligentsia's sincere and creative searchings. But is there any inside the Church? The beginning of sobornost is the Tri-Une God, the Holy Trinity: in human nature, which is intrinsically individualistic, only God himself can arouse a real, free desire for sobornost.

But this will be possible only when man is free and able to devote himself all the time to God, to entrust Him with arousing in people the most profound and intimate desires and thoughts, beginning with the original will to live and be. Original sin is precisely that Man rejected this and began to look for the foundation of his being in all sorts of other things: in nature, in the national, in the Weltgeist, in himself, only not in Got. Thus a vicious circle arose, condemning man to destruction, to the loss sooner or later of the will to live, which lies at the basis of man's existence.

The sobornost of the Church is rooted in Communion in the nature of Jesus Christ. "The Church is the Eucharist," said one of the ancient fathers. It is no accident that the restoration of sobornost in the Russian Church began with the "Eucharistic revival", a movement connected with the name of that great saint of the pre-revolutionary period, Father John of Kronstadt. After Seraphim of Sarov, Ambrose of Optino and Theophanes the Recluse, John of Kronstadt is the type of Hesychast zealot in which experience of knowing God is combined with theological intellect, spiritual "reclusion" with varied service of the world. What was new and unheard-of in the history of the Russian Church was the fact that John of Kronstadt, a typical "venerable" monk in the nature of his spiritual feat, was not a monk at all, but a married "white" priest. An ardent preacher of the Eucharist, Father John witnessed with all his being that the human body together with the soul is called to sanctity, which does not exclude married life. The spirit of Manichaeism, squeamish with regard to Divine creation, a spirit which poisoned the religious psychology of a believing people, was rejected here totally. In the writings of Gregory Palamas the Grace of God, which he understood as the Divine Energy, says to a believer:

"Do you not want to trust yourself to me completely as a monk?... And with a chaste wife beloved by you I greet you and accept you none the less..."

The 20th-century Russian Athonite zealot, the elder Siluan, wrote of John of Kronstadt:

"Some think badly of Father John, and in so doing offend the Holy Spirit Who dwells in him and lives after death. They say that he was rich and dressed well. But they do not know that he in whom the Holy Spirit dwells is not harmed by riches, for his soul is all in God, and it was changed by God and forgot its riches and fine dress. Happy are those who love Father John, for he will pray for us. His love of God is ardent; he is all in a flame of love".Archpriest Sofrony. The Starets Siluan. Paris. 1952, p. 195.

As a result of Father John's great authority and influence the Eucharist again became the focal point of church life. He demanded that people take communion as often as possible, preferably once a week, for which he greatly reduced the requirements of fasting before communion; he recommended general confession, allowing priests to give communion to a large number of believers at once. This was a change in the main guidelines of the parish consciousness, if one remembers that before it was considered quite enough to take communion once a year, and communion itself was regarded as an addition to Lent. The "Eucharistic revival" returned the center of gravity of church life from psychology to ontology, from moralism to synergetic spirituality.

A powerful upsurge of Hesychasm under the name of lmyaslavie came to Russian from Mount Athos at the beginning of the 20th century.

Among the many Russian monks on Mount Athos at that time a dogmatic dispute arose on the nature of the name "Jesus". The lmyaslavtsy ("name-extollers") claimed that it was Divine, whereas the lmyabortsy ("name-combatters") denied this, and most aggressively too. this was essentially a continuation of the Palamite disputes on the 14th century of the Divine or human nature of the light which Jesus showed his disciples on Mount Tabor.

The disorders which arose on Mount Athos necessitated the intervention of the Greek police. More that 600 lmyslavtsy were forcibly sent to Russia in order to be judged by the church authorities. They found defenders in court circles. The matter received a lot of publicity and was even discussed in the State Duma, much to the embarrassment of "enlightened" deputies, who were amazed by this, as they put it, "return to the Middle Ages".

The matter ended with the Holy Synod adopting an extremely negative attitude to lmyaslavie, making use of the inaccuracy of the theological formulations with which the Russian Hesychasts tried to express their experience of knowing God. The scholastics on which the theological consciousness of the Russian clergy was based left no place for such religious experience. When similar disputes arose in Byzantine it took great efforts of theological thought, crowned by the works of Gregory Palamas, to express, argue and establish in words the Hesychasts spiritual experience. The Russian lmyaslavtsy had no knowledge of Palamas dogmatic doctrine, however. Nor had he been studied in their seminaries by the members of the Holy Synod who found the lmyaslavtsy guilty of "heresy" (the Synod members included Archbishop Sergius Stragorodsky). Fragments of the dogmatic resolutions of the Constantinopolitan "Palamite" councils were first translated into Russian by the philosopher Alexei Losev in the late 1920s! The lmyslavtsy were defended by Father Sergius Bulgakov and Patriarch Tikhon felt sympathy for them, but this was already too late. In the Synod's resolution of 1911 the lmyaslavtsy were found guilty and sent "for correction" in small groups to various Russian monasteries. The result was that their practice of prayer spread throughout the whole of Russian monasticism. The main base for Russian Hesychasts became the numerous monasteries in the Caucasus mountains, which relied for support on the mighty monastery of Novy Afon in Abkhazia.

* * *

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------